![[Translate to Englisch:] August Macke Signatur](/assets/content/0_signatur_macke.jpg)

life and work

AUGUST MACKE 1887–1914

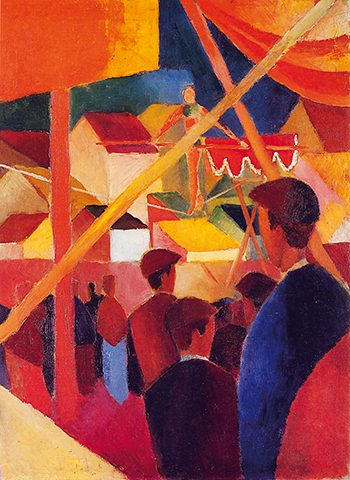

August Macke is one of the most important pioneers in the world of art at the beginning of the 20th century. He tirelessly experiments with color and form in his quest to invent a new language of art. The well-read and inquisitive young man searches for a means of artistic expression in line with the revolutionary progress achieved in the intellectual and scientific areas. To accomplish his purposes Macke frees himself of middle-class conventions and prevailing conservative ideas of art. Above all, the French modernists become his most important source of inspiration.

I. Balancing at the Edge of the Abyss

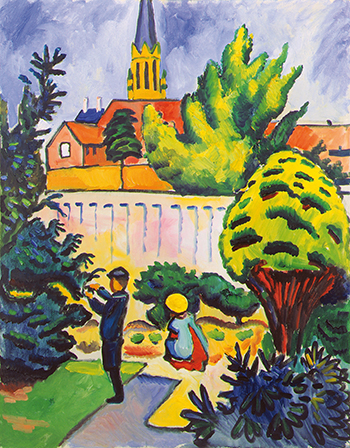

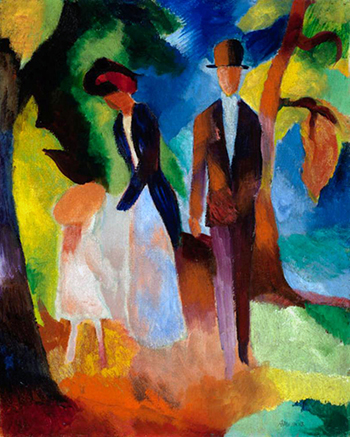

Macke sees happiness as living in the circle of the family with his wife and two sons, and he defines art and living as “instilling joy into nature.“ This positive outlook, particularly in Macke‘s years in Bonn from 1911 to 1913, takes on a characteristic accent that feeds into his art. The images in Macke‘s compositions show variations and multifaceted representations of an earthly paradise. His works become visions of a world in harmony. And, as “songs on beauty” (Macke), they are simultaneously counter-concepts that stand in opposition to an age marked by technical innovation and industrialization. While the great International Expositions of the 19th century in Paris and London identified the South Seas and the Orient as distant places of yearning, Macke locates his earthly paradise in the here-and-now of the real world. All turbulent, destructive, and negative elements are banished. The garden appears as a place of leisure and comfort, as an earthly idyll. And just like his scenes depicting lovers and family, the people and animals in Macke‘s zoological garden pictures are also rendered as a harmonious and primal unity. The peaceful togetherness of the married couple that is reflected in Macke‘s pictures, as well as their mutual care and respect, are not always to be expected in middle-class circles of the time. To typify the close bond between the pair, he introduces crouching figures as a new form-vocabulary borrowed from the Orient. In intimate scenes of everyday life, Macke shows us the world of children who appear naturally and unselfconsciously engrossed in play. The parent-child relationship is redefined here, in accordance with a reform pedagogy that no longer regards children as decorative accessories.

Kunstmuseum Bonn

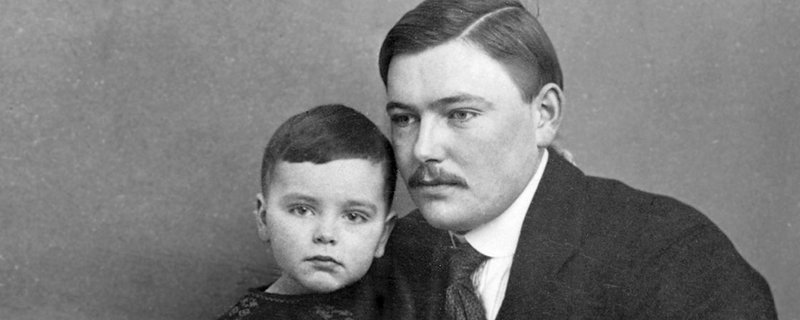

II. Origins, Training, and Artistic Beginnings

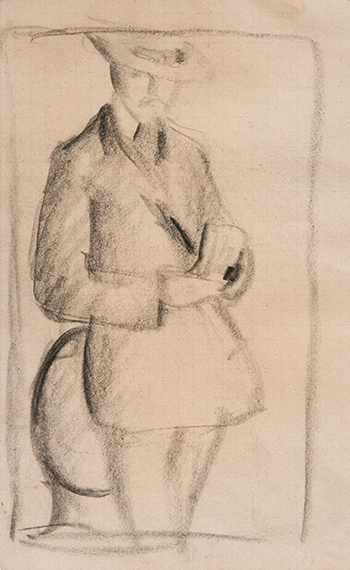

On 3 January 1887 August Robert Ludwig Macke is born in the small town of Meschede in the Westphalian countryside. His two sisters Auguste and Ottilie are several years older. The father is a self-employed building contractor; the mother comes from a farmstead. Macke grows up in Cologne, then in Bonn. His childhood is overshadowed by the economic difficulties encountered by his father‘s firm. As early as grade school Macke‘s only thoughts are on drawing, and he helps design stage sets for school plays. Against the wishes of his father, he drops out of school at age 17 to become an artist and begins studying at Düsseldorf‘s celebrated Art Academy. His professors recognize the young student as an exceptional talent. But the conservative educational program is by no means in keeping with Macke‘s ideas. The ability to depict important historical or current events on canvas still counts, as it has for centuries, as the highest goal of an academic education. Just as important at the Academy are perfect drawing craftsmanship and the creation of exact copies of reality. All of this has little in common with the innovations of the times in which August Macke lives. He looks for other inspirations for his art: in books, in the growing number of art journals being published, in exhibitions, and in nature itself. The latter is a vehicle for conveying mood and meaning in his early pictures and is thus a symbol of his intimate feelings. The shape of a tree, the movement of waves in the water, the harmony of humans with their natural surroundings, and restrained colors underscore the romantic mood as well as the proximity to symbolism.

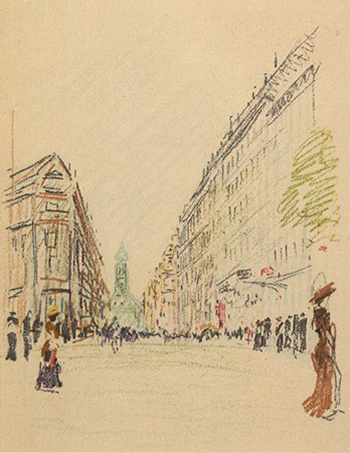

III. Inspired by French Impressionism – Travel to Paris

The impressions Macke receives at Düsseldorf‘s School of Applied Arts where he visits evening classes are more exciting than courses at the Academy. Reform ideas have already entered the curriculum of this center of training for future artisans. At the same time Macke acquires practical experience at the Düsseldorf Playhouse. Its vibrant performance-practice and modern plays make this newly established institution into a reform theater. As set and costume designer, Macke plays a decisive role in implementing the theater‘s concept. “I would create atmosphere with curtains and colors alone, without imitating nature,” is the way he describes his revolutionary ideas. He sees the approach previously taken as a blind alley. He leaves the Academy and also turns down the offer of a permanent position as set designer. This reveals considerable courage and self-confidence. He wants to be free of external constraints and develop his own artistic language, even if that entails considerable risk not only financially. When Macke sees photographs of paintings by French impressionists in 1907, they open up a new world for him—even though the images are only in black-and-white. It is the attention of the artists to their own real-life situations and their entirely new way of painting that make the pictures for him so fascinating. And he consequently decides to travel immediately to Paris, the mecca of modern art. Like so many of his young contemporaries who are disappointed by the norms of the academy he stands before original paintings at the shops of the art dealers DurandRuel, Vollard, and Bernheim-Jeune and drinks in their effect. The Café du Dôme has even become a German meeting place for those looking for new solutions, whether artists, dealers, or collectors. Macke learns to see in a new way and turns toward an impressionist painting of light. On two more visits to Paris, in 1908 and 1909, he intensifies his discourse with modernism.

Museum Ostwall im Dortmunder U

Kunsthalle Bremen

Sigh, Paris is surely the loveliest city in the world. […] I‘m becoming fonder and fonder of the impressionists.

August Macke 1907 from Paris

Stiftung Sammlung Ziegler, Kunstmuseum Mülheim an der Ruhr

I‘m now more convinced than ever of the quality of the French School.

August Macke 1910

IV. Chromatic Imagery with Fauvist Echoes

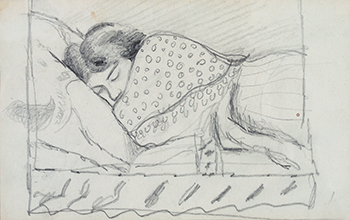

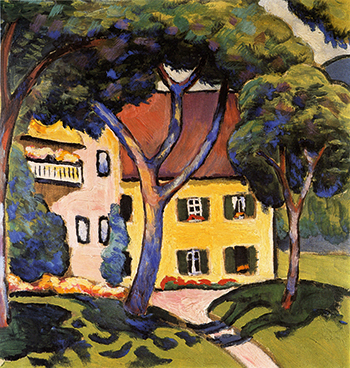

Impressionism and Japonism inspire Macke‘s enthusiasm and liberate him from traditions. But he senses that this is not the end of his artistic development. After completing his year of military service, he opens up a new chapter in his life and embarks upon a new phase in his art. In 1909 he marries his childhood sweetheart Elisabeth Gerhardt. Elisabeth‘s pre-marital pregnancy—a scandal back in those days—occasions the young couple to leave Bonn. They consider living in Paris but housing there is too expensive and they ultimately decide to move to Tegernsee near Munich. Elisabeth is his inspirational muse, his model, and, in Macke‘s own words, his “second self.” Images he captures on paper and canvas also include his surroundings and everyday household objects that he arranges in the living room for lack of a studio. Color lights up the surfaces of his works and begins to take on a life of its own. An overall harmony of chromatic outlines and unusual image segments confront viewers. His pictures reveal the influence of the French fauvists, the modern exhibition group around Henri Matisse in Paris whose works fascinate Macke in Munich in February 1910. But yet another show has an effect on him: the exhibition “Masterpieces of Mohammedan Art,” to which Henri Matisse even travels from Paris to Munich to see. At the beginning of the 20th century, such contacts with foreign cultures inspire modern artists just as art philosophies that differ widely from those of the European tradition. The term “expressionism” is launched around the year 1910 to describe the new stylistic direction and to contrast it with impressionism. At the end of 1910 Macke moves back to Bonn with his wife and little son, where his mother-in-law makes available a small house on the premises of the company owned by her family. He converts the top floor of the house into a studio designed to accord with his own ideas.

After receiving the offer of a studio designed according to his own ideas August Macke decided at the end of 1910 to leave Tegernsee and move back to the home town of Bonn with his wife Elisabeth and little son Walter. His mother-in-law made available to them a small house built in late classicist style on the edge of the premises of the Gerhard family‘s factory. Up to the time when Macke was called up to active military service on 2 August 1914 the new house was headquarters for his many efforts to forge networks in the larger art community. Artist friends like Robert Delaunay, Max Ernst, and many others were frequent visitors. Some of his most well known paintings were done in the bright top-floor studio, and during a visit by Franz Marc in 1912 the two artists painted a large paradise mural on a four-meter wall space. The large garden outside was the children‘s playground-paradise and an important motif for the artist.

V. National and International Networks Artist Friendship between August Macke and Robert Delaunay

Modernist currents, artists, dealers, and collectors — all influenced by the French avant-garde — arouse not only displeasure in Germany‘s Wilhelmine Empire — they are also seen as currying favor with the hereditary rival and arch-enemy France. “Insane”, “deranged”, and “degenerate” are the captions used by the press to describe expressionist artists like August Macke and their work. Excluded from official participation in exhibitions, they have to market their works themselves and begin to found independent groups. Between 1911 and 1913 Macke establishes himself as an important activist in the politics of the art world and a talented networker in the Rhineland, Munich, and Berlin. Rhetorically clever, extroverted, and likeable, he establishes contacts, organizes exhibitions, and gives talks. “He is a fine promoter and skillfully makes his case,” is how Russian colleague Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) approvingly describes him. New groups of art buyers have to be reached and, above all, an understanding for modern art must be encouraged. With this in mind, German modernist artists form networks, also including counterparts in other countries. Close contacts are established not only with Russia, Switzerland, and Scandinavia but above all with France and Paris. Macke befriends Robert Delaunay, whom he visits together with Franz Marc in Delaunay‘s Paris studio in 1912. In January 1913 Delaunay, together with Guillaume Apollinaire, stops to visit Macke in Bonn. This is the start of an ongoing dialogue between Macke and Delaunay on art as well as their personal lives and they collaborate on building an international network of modernists. Delaunay is thus repeatedly invited to show his modern paintings at exhibitions of avant-garde art organized by August Macke and his artist friends and is represented in the traveling exhibition of the Blauer Reiter (1911|12) and at the legendary Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon in Berlin (1913). Wealthy Berlin art patron Bernhard Koehler, uncle of Macke‘s wife and one of the few people collecting “living art,” provides Macke and his friends with financial support for their exhibition and book projects. He is also Macke‘s most eager buyer. And: he purchases two of Robert Delaunay‘s paintings for his collection.

Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden

Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen

© Städel Museum, Frankfurt a. M.

An artwork must be a good fabrication of nature, a selection well made, a mirror of sensations.

August Macke um 1912

VI. Cubist and futurist styles open up new possibilities

Industrialization and technical inventions are changing the look of cities and people‘s everyday lives. Around 1911 Macke looks for new artistic means of visually documenting this transformation. He finds inspiration in the French and Italian avant-garde: in the cubists and futurists. On a trip to Paris with artist friend Franz Marc he sees their work at art dealers such as Vollard. And works of Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso and the futurists are also being shown in various small gallery exhibits in Germany. In his own drawings and paintings Macke then uses stylistic means such as the fracturing of object forms into individual parts; simplification of objects to lines; rhythmic repetition of forms; and small, chopped, geometric snippets. While simultaneously showing quick- paced, clamorous, and pulsating hectic along with technical advances, this lets him illustrate movement as an almost abstract pattern or as an environment that seems to collapse upon his figures. Numerous one-man shows and participations in exhibitions in 1912 and 1913 demonstrate that the open-minded art scene welcomes his work. But Macke is frustrated that his works are not selling: “By the way, with what I earn from painting, it would be better just to sit around and do nothing.” Endurance is required to ignore repeated hostility, bear up against traditional attitudes, and confidently continue along his artistic path, particularly since Macke has to contribute his share to supporting the family with two small sons. Monthly stipends from his wife‘s wealthy relatives cover only basics. But he remains self-assured: “What others think about my pictures no longer interests me.”

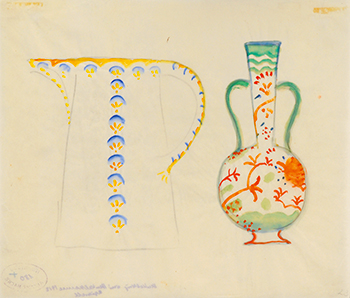

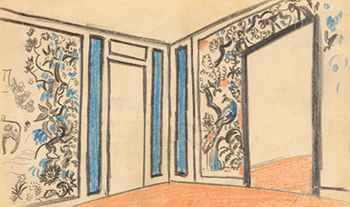

VII. Handicrafts as Part of Everyday Living

For Macke, art and handicrafts are a “form of living” and belong together. An important goal of the expressionists is to design living environments as total works of art in accordance with their own modern ideas. In his bright studio in Bonn with its large skylights Macke works not only at the easel but also at the carpenter‘s bench. He paints porcelain and drafts scenes for needlework that he often sketches directly onto the textile. Macke made his first drawing for embroidery as early as 1905 — out of dissatisfaction with old-fashioned motifs. His wife Elisabeth and her mother and grandmother do the embroidering. At a talk given by Macke, Elisabeth even wears a modern reform dress modeled after his sketches. Moreover, Macke designs door fittings, cabinet attachments, and jewelry, and makes furniture, cushions, and rugs for private use. But the goal is for modern-designed products to replace traditional and out-of-date patterns in the commercial sector as well. The main objective is to restore Germany‘s reputation, which had been tarnished in the 19th century because of products‘ inferior quality and antiquated appearance. Inspired by the reform movement of the “Deutscher Werkbund”, Macke prepares drafts in 1912 of functional modern design for everyday tableware manufactured for export markets. “I‘m doing porcelain now,” he writes to his patron in Berlin. He builds a reputation as designer and in 1913 is asked to draft the concept for the interior decoration of a tea salon in Cologne. Color sketches and numerous drafts give us an idea of Macke‘s design scheme which, however, is never implemented owing to the outbreak of the First World War.

Kunstmuseum Bonn

The work of art is a simile of nature, not a reproduction. […] it is the thought, the independent thought of a person, a song on the beauty of things.

August Macke 1913

VIII. Earthly Paradise

Macke sees happiness as living in the circle of the family with his wife and two sons, and he defines art and living as “instilling joy into nature.“ This positive outlook, particularly in Macke‘s years in Bonn from 1911 to 1913, takes on a characteristic accent that feeds into his art. The images in Macke‘s compositions show variations and multifaceted representations of an earthly paradise. His works become visions of a world in harmony. And, as “songs on beauty” (Macke), they are simultaneously counter-concepts that stand in opposition to an age marked by technical innovation and industrialization. While the great International Expositions of the 19th century in Paris and London identified the South Seas and the Orient as distant places of yearning, Macke locates his earthly paradise in the here-and-now of the real world. All turbulent, destructive, and negative elements are banished. The garden appears as a place of leisure and comfort, as an earthly idyll. And just like his scenes depicting lovers and family, the people and animals in Macke‘s zoological garden pictures are also rendered as a harmonious and primal unity. The peaceful togetherness of the married couple that is reflected in Macke‘s pictures, as well as their mutual care and respect, are not always to be expected in middle-class circles of the time. To typify the close bond between the pair, he introduces crouching figures as a new form-vocabulary borrowed from the Orient. In intimate scenes of everyday life, Macke shows us the world of children who appear naturally and unselfconsciously engrossed in play. The parent-child relationship is redefined here, in accordance with a reform pedagogy that no longer regards children as decorative accessories.

IX. Artistic Synthesis

To devote himself once again entirely to art without the distraction of behind-the-scene art politics, Macke and his wife and two sons depart from the Rhineland‘s hustle-bustle in October 1913. They take up residence on Lake Thun in Swiss Oberhofen for eight months. Rosengarten House, where the apartment is located, stands lakeside opposite an impressive panorama of Swiss Alps. Inspired by the “sunlight flooding through the windowpanes” (Macke) in the paintings of Robert Delaunay, he develops his own unique art philosophy shortly before the outbreak of the First World War. Nature remains his compass as experienced reality, but he now alters and combines motifs. By assembling individual forms into a painted collage, new image-worlds emerge in keeping with his ideas. While appearing to be realistic, they are imaginary. In Macke‘s shop-window pictures the influence of his friend Robert Delaunay can clearly be seen both in terms of motifs and in the prism-like fragment- ation of form and color. But Macke translates the abstractions of the French artist into a contemplative and buoyant image-world. Since dull shades of gray largely predominate in real-world facades and street scenes, the chromatic freshness in Macke‘s pictures is to be interpreted as a metaphor. The legendary trip to Tunis undertaken in April 1914 by Macke with his friends Paul Klee and Louis Moilliet lasts fourteen days. The sunlight of southern shores, the exotic motifs — the artists feel they are living in a fairytale. Macke writes: “I‘m producing like the devil and feel a joy in working that I‘ve never known.” He brings home countless sketches, watercolors, and photographs, which he utilizes later on in the studio in Bonn.

Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe

LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur

Westfälisches Landesmuseum, Münster,

erworben mit Unterstützung des

Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen

LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur

Westfälisches Landesmuseum, Münster

Our most welcome objective is to unlock the spatially defining energies of color rather than contenting ourselves with somber light-dark effects.

August Macke 1913

Museum Ludwig, Köln, Sammlung Haubrich

Kunstsammlung NRW, Düsseldorf

War is a thing of indescribable sadness.

August Macke 1913

X. First World War

After returning to Bonn in the summer of 1914 Macke produces his most famous pictures in a burst of creativity. The artist sees it as his respon-sibility to help shape modernism by means of a new esthetic and paints motifs such as children against the backdrop of an industrial harbor landscape, or a modern iron lattice tower positioned alongside an ancient gothic cathedral. These are less a display of the negative consequences of progress or a sign of isolation and alienation than they are a statement of new possibilities. When Austria declares war on Serbia at the end of July 1914 in the wake of the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Macke senses the oncoming end of an era and the approaching rupture of his artistic efforts. There is no avoiding the immediate call-up into the army after the German Empire orders mobilization on 2 August 1914 — Macke is a trained reservist in the rank of sergeant. At first a certain degree of enthusiasm can be felt — despite the close friendships and ties to French and Russian artist colleagues. Hopes are that the War might sweep away the encrusted past and finally make room for a new beginning. But after the first major battle, Macke is completely disillusioned. Euphoria yields to despair in view of “the horror.” Macke is killed in Perthes-lès-Hurles in Champagne on 26 September 1914, just seven weeks after the outbreak of hostilities. On the easel in his studio a somber looking painting remains unfinished. After Macke‘s death Elisabeth is left with their two little sons. She has not only lost the love of her life, she must also look after her young family. In addition, the burden of administering her husband‘s artistic legacy now rests on her shoulders. In a powerful and moving memorial Macke‘s friend Franz Marc bewails the irreplaceable loss to German art: “With his death one of the most promising and daring lines of development of our German art has been abruptly severed; none of us are capable of carrying it forward.” Two years later Marc too is killed on the battlefield.

XI. Aftermath

The esteem for August Macke among modernist artist colleagues is enormous. But only few collectors actually purchase his paintings. The only exception is Bernhard Koehler, who owns more than 50 works by Macke alone. Not a single museum has acquired one of his paintings during his lifetime. The artist has given away many of his paintings as gifts in gratitude to collectors or for the organization of exhibitions. The appreciation of expressionist art does not begin until after the First World War. The artists for whom no understanding was previously shown are now appointed as professors at the art academies which have finally been reformed. And Macke‘s pictures now enter the in- ventories of the museums. But only for a short time, for these works are removed from the public collections and confiscated by National Socialists as part of the “Degenerate Art” campaign in 1937/38 and the traveling exhibition of the same name. To generate hard currency, the National Socialists order the auctioning off in Switzerland of artworks they classify as “degenerate” or their sale by a specially commissioned art dealer. After the Second World War the museums must rebuild their holdings of expressionist art. The fate of many pictures remains unknown, some occasionally resurface on art markets. Macke‘s art begins to undergo a process of reappraisal and his work increases in value, above all in the 1990s. Macke exhibitions are genuine blockbusters nowadays. Paintings from his final years of creativity prior to the First World War, the “typical Mackes” that have meanwhile entered into the public‘s collective memory and become part of many households through purchases in museum shops as prints on mugs and in calendars, now fetch prices on the art market that exceed millions and can hardly be paid by publicly financed museums.

Text: Ina Ewers-Schultz